| CHAPTER 6. WATER |

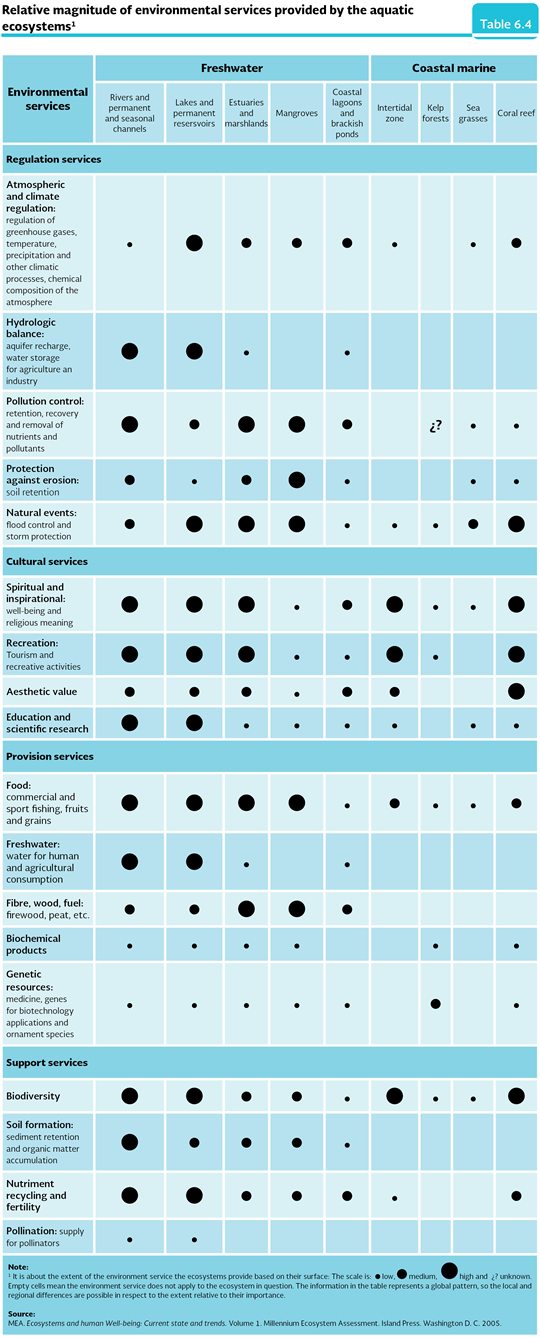

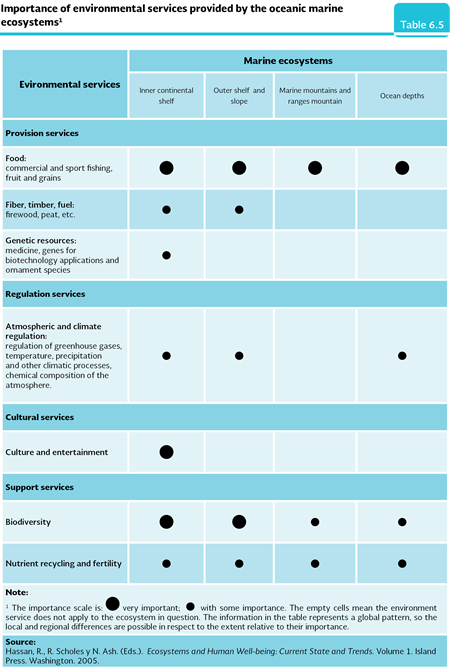

ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES PROVIDED BY AQUATIC ECOSYSTEMS Although traditionally the issues related to the availability and quality of water and the aquatic ecosystems (both continental and oceanic) are treated separately, they are closely related. The aquatic ecosystems, both the freshwater ones and the coastal and oceanic ones, participate in an important way in the hydrological cycle, acting as the most important reservoirs of water and as the primary sources of steam that reaches the atmosphere and then returns to them in the form of precipitation and runoffs. In this sense, they act directly and indirectly over the local and regional water balances, in other words, over the availability of water. At the same time, they are the receptors and filters of the pollutants that the waters that run and reach them bring along, purifying them and contributing to improve their quality. In the Mexican territory, a large variety of freshwater ecosystems are represented: from the ones developed in rivers, lakes, dams and ponds, until those which are found in the terrestrial areas and have a large water influence, such as the marshland, popal and peten vegetation. The aquatic ecosystems of salty waters must be added to the former ones, such as the mangrove, besides of the fully marine, such as the coral reefs, the sea grass beds and the pelagic ecosystem, just to mention some of them. A full description of these ecosystems, their biological importance and their current situation may be found in the Natural Capital of Mexico20 published by the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of the Biodiversity (Conabio, 2009). The natural ecosystems, both aquatic and terrestrial, supply a large amount of goods and environment services indispensable for the daily life and the development of societies. These goods and services are the result, in the end, of the biodiversity and the ecological processes that are carried out in a natural way and that keep the ecosystems running. Although the freshwater for human consumption is one of the most important environmental services that the continental aquatic ecosystems supply, there are other not less important (Daily et al., 1997; Wilson and Carpenter, 1999; MEA, 2005; Tables 6.4 and 6.5). For instance, the rivers and lakes are human and merchandise means of transportation, for the electric power generation, food supply (fishes, mollusks and crustaceans, among others) and the irrigation of the farming lands. In the case of the non-estimated services in the market, we must highlight the role they play, for instance, the wetlands as regulators of the control of the avenues that result from the intense precipitation events (what avoids or reduces the human and economic losses as a result of the floods), the maintenance of their biodiversity (which includes not just the species that are used as food or as material sources, but also the ones that support the ecosystems), the nutrient recycling (by means of the biogeochemical cycles), the purification of the water in industrial and domestic waste and the climate regulation at a local and regional level.

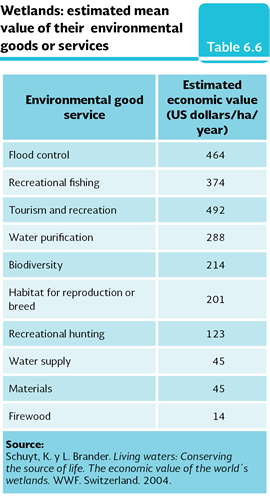

Although the estimates of the economic value of the environment services are scarce, mainly because of the difficulty involved in their calculation, some estimates have been made (Table 6.6). In the case of Mexico, for instance, it has been found that the production, in the fishery, of fishes and crabs in the Gulf of California, it is directly related to the local abundance of mangroves (Aburto-Oropeza et al., 2008).

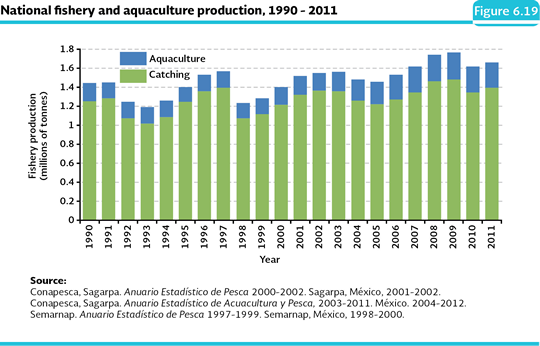

Fishing Due to its economic value and production volume, the fishery products are some of the most important goods obtained from the ecosystems of the continental waters and the oceans at a global level. The fish provides about 20% of the annual intake of animal proteins to about 3,000 million people in the world (FAO, 2012). The preliminary estimates of the world fishing for 2011, based on the reports from some of the principal fishing countries, show that the production (which included both the continental and marine catching and the aquaculture) reached slightly more than 154 million tonnes. In the particular case of Mexico, in the 1990-2011 period the annual fishing production (taking into consideration both the catching and the aquaculture) was 1.47 million tonnes in average (Figure 6.19), what placed it as one of the twenty largest producers in the world with about 1.1% of the total catching for 2009 (FAO, 2010). Taking into consideration the aquaculture, Mexico is ranked in the 26th place in the list of the largest producers at a world level (Conapesca, Sagarpa, 2010).

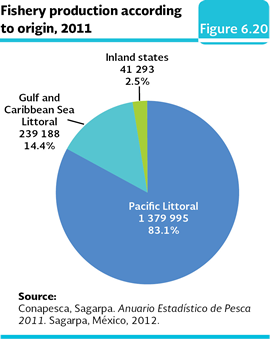

The national fishery production is currently based in the marine catching, in spite of the rapid growth the aquaculture has recorded in the last years. In 2011, 84.2% of the production was for catching (marine and continental) and the remaining 15.8% to the aquaculture (IB 8-1). If the production per littoral is reviewed, between 1990 and 2011, the states in the Pacific provided nearly 76.5% of the national production, with about 1.1 million tonnes per year in average; the states in the Gulf and the Caribbean produced 21.5% of the total (equivalent to 316.4 thousand tonnes per year). The states without a littoral barely reached 2.6% of the total national fishery production, with a little more than 41 thousand tonnes per year in average. In 2011, the largest fishery production was obtained in the Pacific Littoral with 1.38 million tonnes (83.1%), followed by the Gulf and the Caribbean Sea with 238 thousand tonnes (14.4%; Figure 6.20; Sagarpa, 2005-2011; Table D2_PESCA01_01).

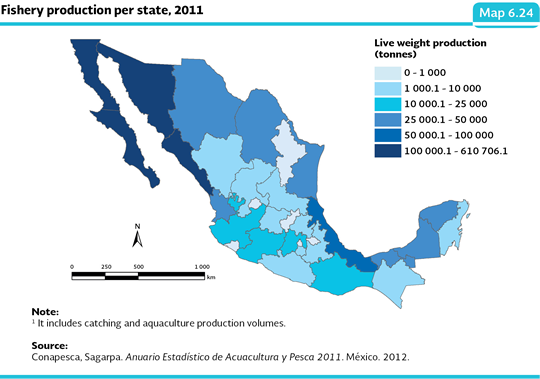

At a state level, the states that in 2011 provided the largest volumes in the national fishery production were: Sonora with 610,706 tonnes (36.8%), Sinaloa with 337,863 tonnes (20.4%), Baja California Sur with 151,186 tonnes (9.1%), Baja California with 135,619 tonnes (8.2%) and Veracruz with 79,268 tonnes (4.8%); which represents a little more than 79% of the national production (Map 6.24; Table D2_PESCA01_01).

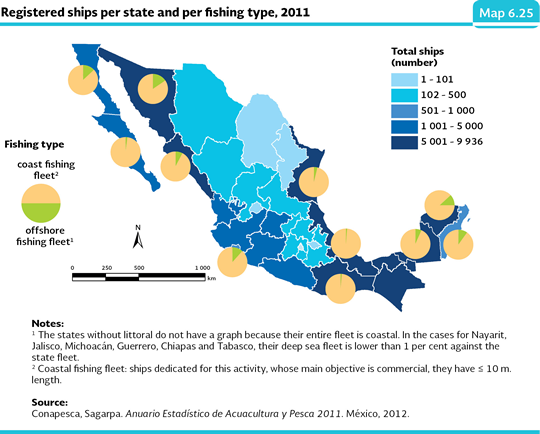

If the contribution of the fisheries to the national production (including the catching and the aquaculture) is analyzed, in 2011 nearly half (48%) of the production (794,566 tonnes) was provided by three fisheries: sardine, tuna and shrimp. Among these, the sardine production was the most important one, accounting over 684.1 thousand tonnes, which is equivalent to 86% of the total provided by these three fisheries. The national fishing fleet increased 10.1% between 1990 and 2011, going from 74,572 to 82,069 ships. In this last year, most of the fleet was made up of coastal fishing ships (96.1%), while the offshore fleet barely represented 3.9% (IB 8-2). From the total national fishing fleet, the shrimp fishing is much bigger than the others: it represents 59.6% of the total offshore fleet, while the tuna fishing ships and the anchovy and sardine catching ships hardly reach a little more than 7.7%. In 2011 there were 1,896 shrimp fishing ships, 70% in the Pacific, and the rest in the littoral in the Gulf and the Caribbean (1,326 and 570 ships, respectively). As part of the fleet, in the Pacific Littoral there were also 234 ships for the flake fishing , 107 for the tuna one and 108 for the sardine one. In the Gulf and the Caribbean Sea there were 805 for the flake fishing21 and 31 for the tuna one in that same year. Per state, in 2011 the biggest offshore fleet corresponded to the states with the largest fishery production: Sinaloa (759 ships), Sonora (516) and Baja California (256) in the Pacific; in the littoral of the Gulf and the Caribbean Sea, Yucatán (664), Tamaulipas (267) and Campeche (257) were the states with the most important offshore fleets (Map 6.25). Concerning the age of the ships, most of them (a little more than 86%) are over 20 years old (60% of them even are older than 30) and less than 2% are 10 years old or even less).

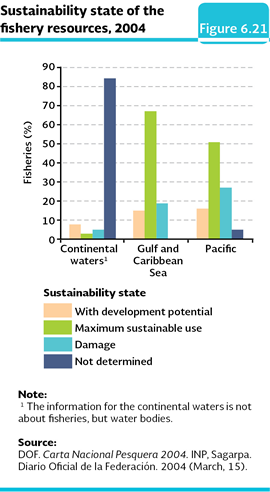

Status of the fisheries The fishery catching may turn into a very harmful activity for the fishery resources when it is done in an inadequate way (FAO, 2009). Some of the most important consequences of the fishery overexploitation are the loss of the productivity and its commercial extinction (Jackson et al., 2001). That is the result of the effect that the catching has on the population of the objective species: decrease of its population size and alterations in its structure of sizes and reproductive condition (García et al., 2003; Godø et al., 2003). The former effects affect the recovery potential as well as the long term viability of the population of the fishery species. In Mexico, from the National Fishery Letter (DOF, 2004), which is based on the fishery generalities (catching areas, equipment, and used fishing arts), as well as several indicators (i. e. catching and catching effort), it was determined the status the several country fisheries held. So, in the Gulf of Mexico and in the Pacific, 19 and 27% of the fisheries, respectively, were found in deterioration conditions, 67 and 51% in maximum sustainable use conditions, and just about 15 and 16% had development potential (Figure 6.21). Concerning the continental water bodies, in 84% their status was not determined, 8% had development potential, 3% maximum sustainable use and 5% was in deterioration (DOF, 2004; IB 8-5).

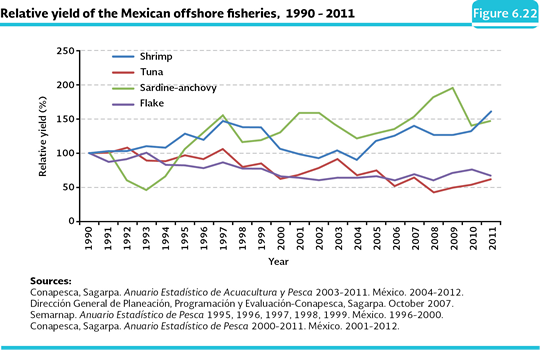

Another indirect method to evaluate the status of the fisheries is by means of the estimation of their yields. The relative fishery yield is defined as the catching obtained in a particular period times the unit of catching effort, standardized with respect to a base year (FAO, 2000). If it is expressed as a percentage, a value of the indicator over 100% suggests the resource may continue developing, while a lower value may mean the deterioration of the fishery. In general, in Mexico the flake and tuna fisheries show, for the period between 1990 and 2008, decreasing yield values, what suggests a deterioration of both fisheries; although in the two years after that their yield increased 45% (it went from 42 to 67); on the other hand, the shrimp fishery shows, in spite of the oscillations, growing yield values that show that it still has exploitation potential; while the sardine-anchovy one, which with fluctuations, had an important increase until 2009 and in 2010 decreased 28% and it recovered 5% in the last year (Figure 6.22; IB 8-4).

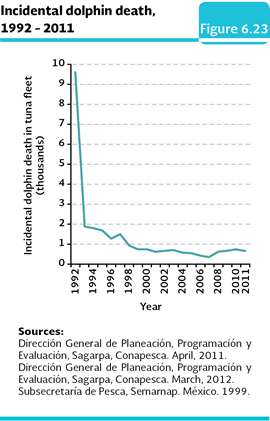

Other fishing impacts In addition to the deterioration of the fisheries themselves, the fishing may have a very severe impact on the coastal and oceanic biodiversity. One of the most serious problems that causes is the incidental catching of organisms without a commercial interest, the so-called accompanying fauna (mainly formed by mammals, fishes, reptiles and invertebrates), mainly because of the lack of screening of the traditional arts. In the case of the shrimp fishery, for instance, the accompanying fauna is made up of about 600 fish species of fishes, mollusks, echinoderms and crustaceans (DOF, 2010). Although it is difficult to accurately determine the damage the incidental fishing has caused in the marine ecosystems, just in 2000 the discarding of the accompanying fauna reached 6,400 tonnes in the Pacific, while in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea was 1,846 tonnes. For 2010, the total reported volume of accompanying fauna was 5,601 tonnes; 4,344 in the Pacific and 1,257 in the Gulf and the Caribbean (DOF, 2010). Some fishing arts also disturb the marine environment and destroy the habitat of many species. The trawling nets sweep the marine bed looking for shrimp and other species of the bottom, what causes that sea grass beds, sponges, corals and urchins, among other organisms, are caught, hurt or taken off the oceanic bed. With the loss of the microhabitats created by sponges and coral, other ecosystems are also lost as well as the recruiting and feeding for other species sites, which affects both their populations and the flow and dynamics of the trophic chains. Although there are not regular data of the area that is annually swept searching shrimp and other species of the bottom, in 2000, it was estimated that just in the Mexican Pacific the dragged surface was almost 550,000 square kilometers (nearly two times the surface of Chihuahua state), while in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea added 187,000 square kilometers (Sagarpa, 2007). Other fisheries like the tuna one may catch endangered vertebrate species, among which are the cetaceans, sharks and marine turtles (Table D2_PESCA04_02). That is why this fishery is under a meticulous supervision carried out by technical observers who guarantee the meeting of the national and international regulations which may allow the reduction of the incidental catching, mainly of the associated dolphins. The efforts made for the protection of these mammals started in the mid of the 1970s, and currently there are two ongoing programs (one national and another international) to progressively reduce the incidental mortality of these animals. Both of them are based on the monitoring of the incidental mortality of dolphins by means of observers since 1991. The Emergency Mexican Official Standard NOM-EM-002-PESC-1999 updates the previous legislation on the issue to protect dolphins in the framework of the Agreement on the International Program for the Conservation of the Dolphins (AIDCP) and the Interamerican Commission of the Tropical Tuna (CIAT) and incorporates the “limit of dolphin incidental mortality” (LMD) per ship as a basic control instrument. In Mexico, during the last two decades, the dolphin incidental death due to the activity of the tuna fishing fleet has decreased 92.7%, going from a little more than 9,560 dolphins in 1992 to 701 in 2011 (Figure 6.23; IB 6.4.1-6). Due to the improvement achieved in the country in the reduction of the mortality of the dolphins, in May 2012 the World Trade Organization (OMC) published the final ruling on the tagged “dolphin safe” that the United States maintains on the Mexican tuna, with the purpose to lift the tuna embargo of our country.

Notes: 20 Available in PDF format in the website: www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/pais/capitalNatMex.html. 21 It refers to a very wide fishery, which covers resources related to both the coastal line and estuarine environments, such as the continental waters (rivers, lakes and dams).

|