Water is one of the most important resources for life in the planet. Human beings depend on its availability not just for the domestic consumption, but also for the functioning and continuity of the agricultural and industrial activities. In the last decades, in order to produce more food and energy, as well as to provide the freshwater service to a population every time more numerous, the demand of the liquid has grown dramatically. Another important problem related to the possibility to use the water is its pollution level, because if it does not have the proper quality, it may exacerbate the water scarcity problem. The water of the surface and underground bodies are polluted by the discharges of water without a previous treatment, of municipality and industrial waters, as well as the water entrainments that come from areas that practice agricultural and livestock activities.

Although the water issue has mainly focused on the human necessities, it is compulsory to highlight its importance as a key element for the functioning and maintenance of the natural ecosystems and their biodiversity. Without water that guarantees their function and maintenance, the natural ecosystems degrades, lose their biodiversity and so, they stop the provision or reduce the quality of the goods and environment services that support societies.

FRESHWATER IN THE WORLD

Reserves of freshwater

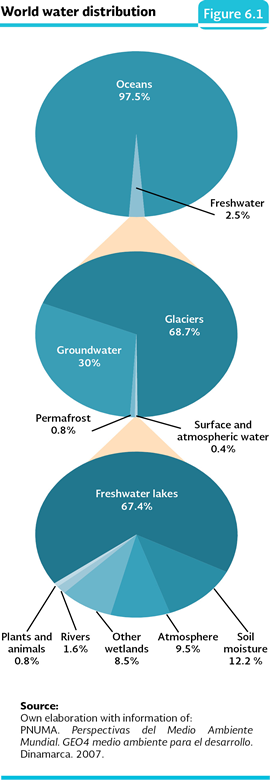

It has been estimated there are about 1,400 million cubic kilometers of water in the planet, and just 2.5% of them are fresh-water (PNUMA, 2007). This small percentage is mainly located in the rivers, lakes, glaciers, ice sheets and aquifers of the world (Figure 6.1). Almost three quarters of fresh-water are contained in the glaciers and ice sheets, out of which, 97% of them are practically inaccessible for their use, because they are located in the Antarctic, the Arctic and Greenland. However, many of the continental glaciers, as well as the ice and the perpetual snow in the volcanoes and mountain ranges become an important source of water resources for many countries.

In the planet 30% of the existing fresh-water is groundwater, 0.8 at Permafrost1 and just 0.4% to surface waters and in the atmosphere. If we take into consideration non-frozen freshwater (31.2% of volume of total freshwater), the ground one represents 96%, water that becomes important as the supply of streams, springs and wetlands, as well as a fundamental resource to satisfy the demands of water of many societies in the world. While the surface waters (lakes, reservoirs, rivers, streams and wetlands) just retain one per cent of non-frozen fresh-water; among them, the lakes of the world store over 40 times the water contained in rivers and streams (91,000 versus 2,120 km3) and about nine times what it is stored in the swamps and wetlands. Although the water in the atmosphere is equivalent to a meaningful volume lower than the water found in the lakes, it is very important because of its role in the climate regulation.

Note:

1International Permafrost Association (IPA) defines it as cold soil that remains below 0°C for 2 or more consecutive years (van Everdingen, 1998). According to the IPA, permafrost is not synonym of frozen soil but of “cryotic ground”, in other words, of soil that tends to form ice, but it does not necessarily has it (Milana and Güel, 2008).

|