THE DESERTIFICATION PROBLEM

Although the soil is the place where a large amount of the primary activities is carried out (agriculture and livestock) from which our food is produced, and besides it is the support for the housing, industrial, highway and recreation infrastructure, its degradation is a part of a major process called land degradation. In this sense, "land" must be understood as the specific area of the terrestrial bark which has particular characteristics of atmosphere, soil, geology, hydrology and biology, where the results of the past human activity and the interactions among all the elements are shown (UNCCD, 1994).

For the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the land degradation is "the reduction or loss of the economic productivity and loss of the complexity of the terrestrial ecosystems, including the soils, the vegetation and other biotic components of the ecosystems, as well as the ecological processes, biogeochemicals and hydrological processes that take place in them".

When the land degradation is produced in the arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas, we are talking about desertification. Under this definition, desertification is not the transformation of several ecosystems into deserts, but the loss, most of the times irreparable, of the soil productive functions, the alteration of the biological cycles and the hydrological cycle, as well as the decrease of the supply and the amount of environment services generated by the ecosystems.

There is not a linear cause and effect process that allows explaining desertification fully; however, complex interactions that work as the process engines have been detected. Such engines are climate variations (such as the low soil humidity, the changing precipitation patterns and the high evaporation) and the human activities (such as soil overexploitation due to the agricultural activity, the overgrazing, the deforestation, the inadequate use of irrigation systems, the market trends and even sociopolitical dynamics; UNCCD y Zoï, 2011). In final point, poverty may play the role as a cause and consequence of desertification.

In Mexico, according to the Law of Sustainable Rural Development, the desertification concept applies to all of the existing ecosystems in the national territory; since the loss of the land productive capability is not restricted to dry zones (DOF, 2012). However, it is important to note that the former does not lower the priority the UNCCD establishes for the arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas to delimit the regions that may suffer desertification.

The most important consequences of desertification go from a food production decrease, infertility and soil salinization, reduction of the capability of natural land recovery, increase of the floods in the low parts of the basins, shortage of water, sedimentation of water bodies, worsening the health problem due to the dust transported by the wind (i. e. eye infections, respiratory diseases and allergies) and alteration of the biological cycles, up to the loss of the means of subsistence of the societies, which may contribute to stimulate the migration (UNCCD y Zoï, 2011).

The world fight against desertification is headed by the UNCCD, which was implemented in the decade of the 1990s. As of May, 2012, 195 countries had approved, agreed, ratified or had joined as members of such Convention, among them Mexico, which ratified it in 1995 (UNCCD, 2012). The UNCCD is a unique instrument focused on both the attention to the land degradation and the social and economic problems this process generates. It has four strategic goals: 1) to improve the living conditions of the affected populations; 2) to improve the conditions of the affected ecosystems; 3) to generate global benefits through the effective implementation of the Convention itself, and 4) to mobilize the resources to endorse the effective implementation of the Convention through the creation of effective alliances among the national and international actors.

Although in our country the first actions of fight against desertification were implemented in the decade of the 70s of the last century through the National Commission of Arid Zones (Conaza-Sedeso, 1994), it is until 2005 that in the framework of the agreements signed before the UNCCD, the National System of Fight against the Desertification and the Degradation of the Natural Resources (SINADES) is created. In this system diverse public institutions converge (Semarnat, Sagarpa, INEGI, SRA, Sedesol, Conafor and INE), social organizations (RIOD-Mex, CNC, CNPR and CCDS) and the academic sector (CP, UA-Chapingo, UAAAN and ITESM). The SINADES is coordinated by the Semarnat, through the National Forest Commission (Conafor), which works as a focal national point before the UNCCD.

SINADES aims for a major involvement of the society in the sustainable management of lands, by means of the following goals: a) to contain and revert the desertification and the degradation of lands through integral recovery programs and foster the sustainable production; b) to promote that the producers adopt productive practices and systems that preserve and improve the natural resources; c) to coordinate the efforts against desertification and degradation of the natural resources where the Federal Government and other Government entities take part, as well as organizations of the civil society; and d) to promote the creation and strengthening of an environmental conscience emphasizing the attention of the society on the desertification problems and the degradation of the natural resources.

Dry lands distribution

The arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas, generically named dry lands, are characterized for having particular climate conditions, such as the scarce and irregular precipitation, a great difference between the day and night temperatures, soils with little organic matter and humidity, in addition to a high potential evapotranspiration. These characteristics allow human settlements to establish around the few available water sources (such as rivers, springs or wells) which are usually overexploited or polluted.

There are different definitions of dry lands, which may irremediably lead to different figures about the extent of the surface affected by the desertification or about the affected population. In this chapter the UNCCD criteria was adopted, which classifies the dry lands depending on their aridity index7 as arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid. This classification is based on the World Atlas of Desertification (PNUMA, 1997), which states that the dry lands are those areas where the aridity index is lower than 0.65.

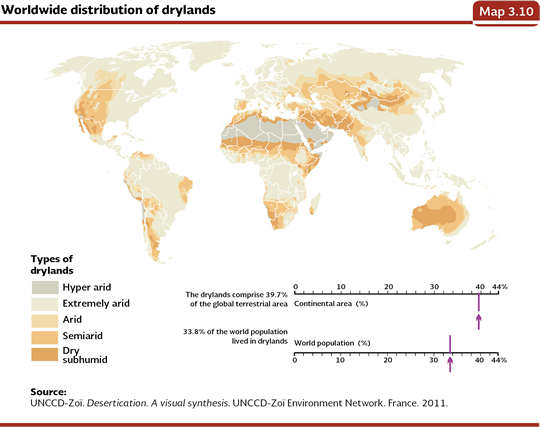

According to the UNCCD (2011), 12.1% of the terrestrial surface of the planet corresponds to arid areas; 17.7% to semi-arid areas and 9.9% to dry sub-humid areas. A little more than 2 billion people live in those areas (about 1 out of every 3 inhabitants of the planet), most of them live in developing countries. Besides, the dry zones host 50% of the cattle and 44% of the agricultural lands of the world, and they are very big land extensions that represent very valuable habitats for wildlife. The largest dry land extensions are found in Australia, China, Russia, The United States and Kazakhstan (Map 3.10).

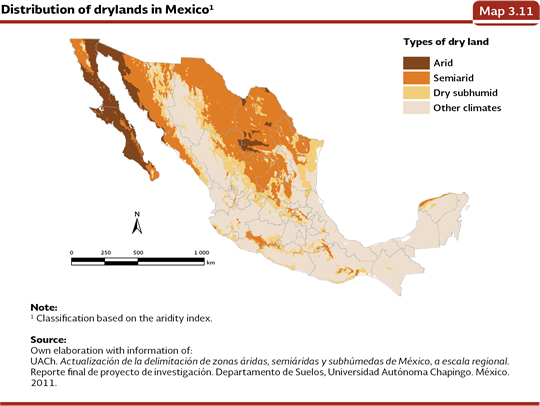

In Mexico, the dry lands (arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid) are mainly found in the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Desert and in the central regions influenced by the effect of orographic shade generated by the Sierra Madre Occidental and Oriental. Based on a study carried out by the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (2011), the dry lands of Mexico (also determined from the already mentioned aridity index), take about 101.5 million hectares8, a little more than half of our territory. Out of this surface, the arid areas represent 15.7%; the semi-arid ones, 58% and the remaining 26.3% corresponds to the dry sub-humid areas (Map 3.11).

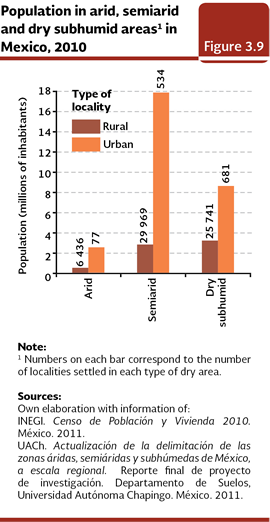

According to the Population and Housing Census 2010 (INEGI, 2011), 33.6 million people inhabited the dry lands of Mexico, which were equivalent to 30% of the country population. 18.1% out of them lived in rural localities and 81.9% in urban localities (Figure 3.9).

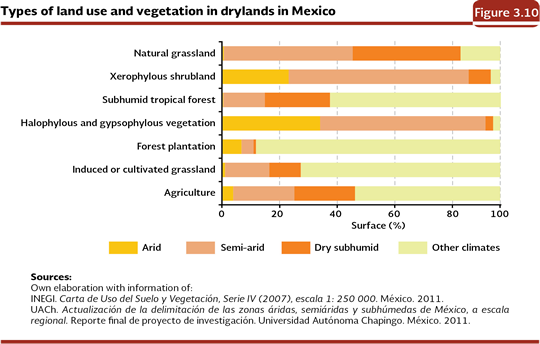

91.5% of the population who live in the dry areas of Mexico is concentrated in the semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas probably because there is a minor water deficit within them, what allows a major economic activity. In fact, a little less than half of the agricultural surface of the country and almost a third of the induced or cultivated grassland are located in this type of areas (Figure 3.10).

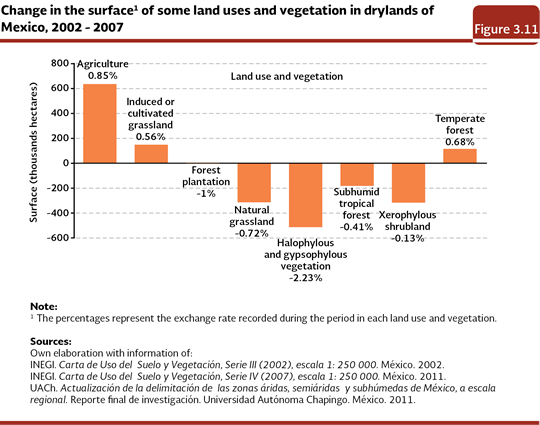

From the natural vegetation that took the arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas in the country in 2002, about a million hectares (mainly of sub-humid tropical forests, natural grassland and halophylous and gypsophylous vegetation) were transformed towards some other use by 2007 (Figure 3.11). Most of this transformed surface corresponded to halophylous and gypsophylous vegetation. In the same period, the induced and cultivated grassland assigned for livestock, grew in more than 148 thousand hectares and the agriculture did the same thing in nearly 650 thousand hectares.

Extension of the desertification

The UNCCD estimates that between 71 and 75% of the dry areas of the world is desertified. In the case of Mexico, the estimates of the extent of the desertification may differ, at first, due to the methods that have been used to calculate them. Although, as of today, there is not a specific study about the extent of the desertification in the country, this work considers the soil degradation in the arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas as a desertification estimator, nevertheless, accepting that it is an approximation that just considers one of its elements and the information about the condition of the soil dates back to about ten years ago.

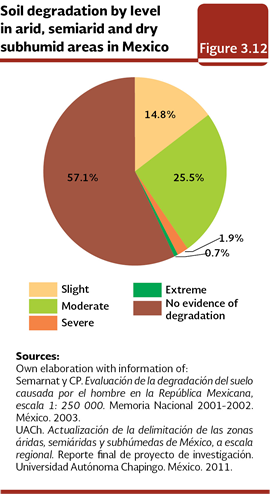

Under these premises, in our country the soil degradation would affect about 43.56 million hectares, that is to say, 43% of the dry lands, which is equivalent to 22.17% of the national territory (Figure 3.12). From the total of dry lands that present soil degradation, 5% is arid, 61.2% is semi-arid and 33.8% is drying sub-humid. However, when the affected proportion is examined with regard to the surface that takes each one of these types of dry lands, the dry sub-humid ones are the most affected (55%), followed by the semi-arid ones (45.3%) and at the end the arid ones (13.8%).

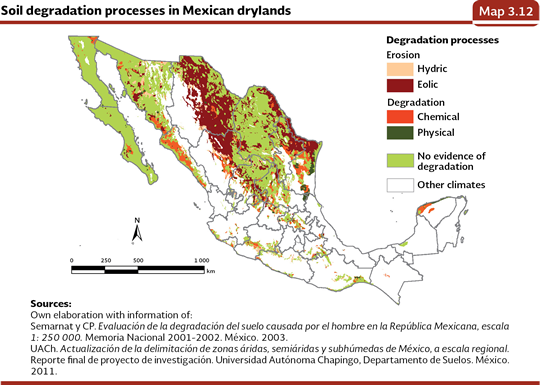

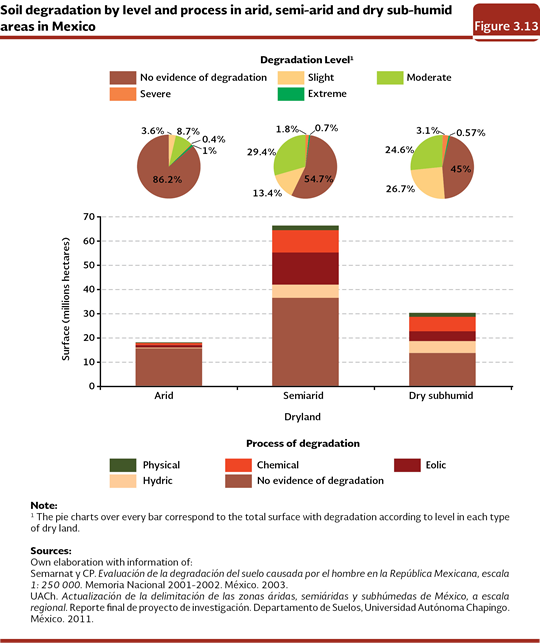

From the surface affected by degradation in the dry lands, nearly 94% was in slight and moderate levels, what suggests that if the elements that cause the degradation of these soils continue working, they could go to the severe and extreme level in the future, where the recovery of their productivity would be practically impossible. In spite of this, in the center of the Chihuahuan desert (near the confluence of the states of Chihuahua, Coahuila and Durango), in the Great Desert of Altar, at the northwest of Sonora and in the Baja California peninsula, it is still possible to find regions of dry lands without evidences of soil degradation (Map 3.12).

Concerning the distribution of the soil degradation processes per type of dry land, the eolic erosion is the dominant process in the arid and semi-arid areas, while the chemical degradation prevails in the dry sub-humid ones (Figure 3.13).

Notes:

7 It is obtained from the quotient between the annual average precipitation and the potential evapotranspiration average. The values between 0.05 and 0.2 correspond to arid areas; between 0.2 and 0.5, to semi-arid areas; and between 0.5 and 0.65 to dry sub-humid areas.

8In the Mexico´s State of the Environmental Report 2008, a zoning based on the Köppen climate classification, adapted for Mexico was used (García, 1988). Taking as a basis the classification above mentioned, a surface of 128 million hectares of dry lands in Mexico was obtained, which is about 65.2% of the territory.

|