| La información más reciente sobre vegetación y cambio de uso del suelo en México, se encuentra en los Indicadores Básicos y Clave. |

| CHAPTER 2. TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS |

CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS AND THEIR NATURAL RESOURCES The extent of the change and historical loss of the natural ecosystems, as well as the application, over several decades, of non-sustainable exploitation schemes, have brought about, unavoidably, the environmental degradation in a large part of the national territory. While these forces are, in the end, the most important because of their effect over the natural vegetation, they are not the only ones. Other activities, such as the ones that are a result of the atmospheric pollution, as well as pollution of soils and area water bodies, mainly, have also had an impact, sometimes meaningful, over the state of the natural ecosystems of the country. The environmental consequences of the removal and degradation of the vegetal cover are clearly seen in Mexico: they go from the deterioration of the scenery itself, until the degradation of the soils and their productive function, the loss of biodiversity, the reduction of the availability and the quality of the area and ground waters and low production of many products that come, directly or indirectly, from the natural resources provided by the ecosystems. In the same way, the vulnerability of many regions before extreme meteorological events, such as torrential rains, floods, blizzards and hurricanes, are caused at some extent, by the deterioration and loss of the natural ecosystems. However, the consequences of the deterioration are not just limited to the environmental sphere, but, due to the given strong dependency between the population and the environment, they go beyond and affect the well-being of the population (see the section Human activities and environment in the chapter Population). The environment degradation is generally accompanied, in the short, middle and long terms, by the loss and the deterioration of the means of subsistence and the life quality of many communities (especially the rural ones), which may lead to social exclusion and poverty situations which may be turned into negative social phenomena for the society as a whole. In this sense, the society development has depended, and it will continue doing it, on the continuous and appropriate supply of the environmental services provided by the ecosystems, which is unavoidably linked to their integrity and functioning. Facing this panorama, it has been evident the necessity to start, from the federal government, strategies that allow to guarantee the permanence of the national natural capital and the continuous supply of the services they provide. In general, there are three lines where the programs and federal actions toward fulfilling such purposes may be grouped. In the first place, we have the instruments which attempt to protect and deter the loss of the remnant area of the natural ecosystems, with which, in addition to safeguarding the ecosystems and the representative species of the national biodiversity, the environmental services from many regions of the country are conserved. Among them, we can find, basically, the protected natural areas, the wetlands included in the Ramsar Convention and the payment for environmental services programs. The second line covers all of the programs that attempt to improve the life quality of the population by means of encouraging the exploitation of the natural resources present in their communities, mainly the forestry and fauna resources, trying to guarantee that this does not surpass the capacity of the same resources to be restored and to keep in levels that allow their extraction in the long term. Among them, the programs of use of the wildlife use and forest development programs. An important step for the development and consolidation of this line was the beginning, in February 2007, of ProÁrbol. This program is mainly aimed at contributing to fight poverty, to recover the forestry resources and to increase the productivity of the forests and tropical forests of the country. Among its efforts, there are efforts oriented to the conservation of the forestry areas, where the pay for environmental services programs mentioned above are included. For more details about this program, its particular objectives and action lines, review the Box ProÁrbol: conservation, recovery and sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems in México (in the Edition 2008 of the Report). In the following sections it will be possible to also find the results of several activities which have been carried out in their different action lines. Finally, the third group of instruments is meant, on one side, to revert the loss of the natural vegetation, basically through the reforestation; and on the other side, to deter the threats against, mainly, the forestry ecosystems, the forest fires and the diseases and pests which damage them. It must also be mentioned that there are other instruments that have been useful, in an indirect way, for the protection of the terrestrial ecosystems of the country: the ecological arranging of the territory and the environment impact evaluations. In the case for the first ones, they work as ecological planning instruments that look for the balance between the productive activities and the conservation of the nature, by means of the conciliation of the aptitudes, priorities and needs of the land uses. On the other hand, the environment impact evaluations are aimed at identifying and quantifying the impacts the execution of several projects may cause to the environment, establishing, in this way, their environment feasibility and determining the conditions for their execution, as well as the prevention and mitigation measures of the environment impacts. Finally, the third group of instruments is meant, on one side, to revert the loss of the natural vegetation, basically through the reforestation; and on the other side, to deter the threats against, mainly, the forestry ecosystems, the forest fires and the diseases and pests which damage them. It must also be mentioned that there are other instruments that have been useful, in an indirect way, for the protection of the terrestrial ecosystems of the country: the ecological arranging of the territory and the environment impact evaluations. In the case for the first ones, they work as ecological planning instruments that look for the balance between the productive activities and the conservation of the nature, by means of the conciliation of the aptitudes, priorities and needs of the land uses. On the other hand, the environment impact evaluations are aimed at identifying and quantifying the impacts the execution of several projects may cause to the environment, establishing, in this way, their environment feasibility and determining the conditions for their execution, as well as the prevention and mitigation measures of the environment impacts.

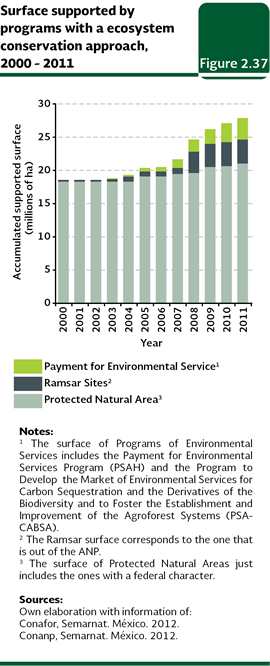

Conservation of terrestrial ecosystems and environmental services The conservation strategy of the terrestrial ecosystems mainly attempts to ensure the protection of the natural areas which are important due to their biodiversity and/or the environment services they provide to the society. Within this strategy, the most important promoted instruments have been the federal protected natural areas (ANP, in Spanish), the wetlands from the Ramsar Convention and the pay per environmental services programs (PSAs in Spanish). As a whole, these instruments protected, as of December 2011, about 27.5 million hectares, which is equivalent to about 14% of the continental national area (Figure 2.37).

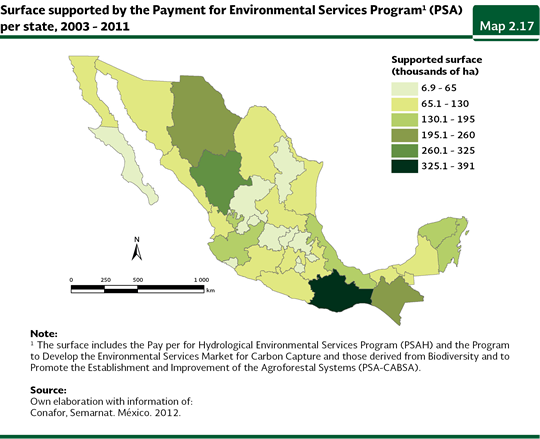

The protected natural areas are one of the internationally most used strategies to maintain the integrity of the ecosystems. These areas are representative areas of several ecosystems, where the original environment has not been meaningfully altered by the human activity, which provide environment services of different types and hold important natural resources or species of ecological, economic and/or cultural importance. At a global level, the protected areas cover 17 million square kilometers, which is equivalent to nearly 13% of the terrestrial area (UNEP, 2011). In Mexico, the growth of the protected area of the terrestrial ecosystems by the federal ANP has been meaningful: it moved from 16.4 million to 20.7 million hectares between 1994 and December 2011, which means, for the last year, around 10.5% of the national continental area (Table D3BIODIV04_12; IB 6.1-6). It is important to note that the protected area of the terrestrial ecosystems included in the ANP in 2011 is 81.2% of the total area included in such instrument, because the remaining 18.8% (4.8) million hectares) corresponds to marine areas (for more details see the chapter Biodiversity). In the federal terrestrial ANPs, the ecosystems mostly represented are the xerophilous shrublands (nearly 7.3 million hectares, 36% of the protected terrestrial area), the temperate forests (4.2 million hectares, 21%) and the sub humid and humid tropical forests (3.1 million hectares as a whole, 9 and 7%, respectively). Along with the development of the federal ANPs, protected areas of state, community , ejidal and private nature have also been protected, which increases the national area under conditions of protection, in addition to the called certified areas (more details about these instruments may be consulted in the chapter Biodiversity, in the section Biodiversity protection). By 2010, 296 ANPs had been decreed at a state level, and 98 of municipality character, which took an area of about 3.3 and 0.17 million hectares, respectively (Bezaury et al., 2009a and b). In the case of the certified areas, by September 2012 there were 324 areas, with a little less than 317 thousand hectares. Mexico also takes part in the international stream of protection of wetlands of the Ramsar Convention, to which it became a member in 1986 which is aimed at the conservation and the rational use of the wetlands, especially those with an international importance in terms of ecology, botany, zoology, limnology or hydrology. By December 2011, Mexico had filed 134 sites before the Convention, which covered around 8.9 million hectares. In the continental territory of the country there are 124 Ramsar wetlands registered, with an area of about 6.6 million hectares, which protect, among other ecosystems, mangroves, marshes, lagoons and river mouths. From them, 63 wetlands are included, totally or partially, within the ANPs, with an area of 3.1 million hectares; while 61 of them are excluded from the protected areas (with an area of about 3.6 million hectares) For more information about the wetlands of the Ramsar Convention, see the chapter Biodiversity). The recent assessment of the importance of the environment services of the ecosystems has led to the design of a group of strategies that attempt, in general terms, that the owners of the lands which sustain the ecosystems that produce certain environment services, receive a pay for this, motivating their protection and avoiding the change of the land use. Mostly, this strategy has been aimed, both in Mexico and the world, at the protection of the basins, the conservation of the forests and the biodiversity and the carbon sequestration. The first step given in the country was in 2003 with the Pay per Hydrological Environment Services (PSAH, in Spanish), under the responsibility of the National Forest Commission (Conafor, in Spanish) and which was a component of the ProÁrbol program. The principal objective of the PSAH has been the maintenance of the hydrological environment services provided by temperate forests and tropical forests, by means of a monetary pay to the owners of the forestry lands which provide them, who are required to keep their land in good conditions, without a change of the land use, during the period when the agreement is established. The support has been directed towards areas of critical basins, with overexploited aquifers or towards those ones which supply towns with over five thousand inhabitants. The Program to Develop the Environmental Services Market for Carbon Capture and those Derived from Biodiversity and to Promote the Establishment and Improvement of Agroforestal Systems (PSA-CABSA, in Spanish)) was the second initiative of its kind and it was implemented in 2004. It promotes the access of the forestry land owners to the national and international markets for environment services related to the carbon sequestration and the biodiversity of the forestry ecosystems. In this case, the pays are granted in order to motivate the owners and holders to carry out actions meant to maintain or improve the supply of the environment services of interest (mitigation of the climate change, conservation of the biodiversity). As a whole, the area benefited, mainly the area of temperate forests, mountain cloud forests and tropical forests, by the pay programs for environment services (PSAH and PSA-CABSA) reached, by December 2011, 3.23 million hectares, out of which, 2.42 million (75%) belong to the PSAH and the remaining 809.6 thousand hectares (25%) belong to the PSA-CABSA. The state area supported by the programs of environment services between 2003 and 2011 is shown in the Map 2.17. The state with the largest benefited area in this period, was Oaxaca (with a little less than 391 thousand hectares, it means, 12.1% of the total area benefited by the program), followed by Durango (269 thousand hectares; 8.3%), Chihuahua (236 thousand hectares; 7.3%) and Chiapas (227 thousand hectares; 7%).

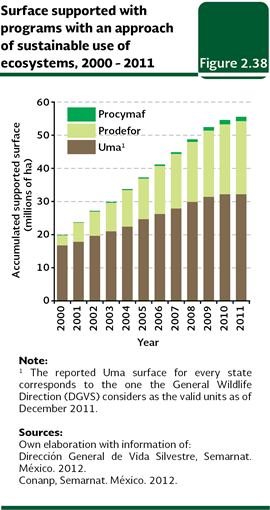

Sustainable use of natural resources from terrestrial ecosystems In Mexico and the world, the natural resources were seen over a long time as inexhaustible sources of economic income. That is why its use, in many cases, has been exclusively ruled by its demand in the market or by the daily needs, not paying attention to their natural capacity to recover from the natural environment variability and from its exploitation rates. As a consequence, the population of many species reduced dramatically, and they even were locally extinguished, what caused a fall in their production or, for the most serious cases, in their definitive commercial extinction. Not just the commercial exploitation carries out the non-sustainable extraction of the natural resources: even certain traditional extraction practices may cause the deterioration of the populations of wildlife, so they also require specific regulations that may allow their use in the long term. In order to achieve the use of the national wildlife under sustainable criteria, several instruments have been designed and implemented which may be grouped in two main axis: the one focused on the management of wildlife of cynegetic or ornamental interest, represented by the Management Units for Wildlife Conservation (Uma); and in the second place, the one which attempts the development of the forestry activity by means of an increase of the productivity and the diversification in the use of the forestry ecosystems, under the responsibility of the Forest Development Program (Prodefor, in Spanish) and the Communitary Forest Development Program (Procymaf, in Spanish). In both axis, it is also sought, as a fundamental objective, the improvement of the life quality of the owners of the lands where the used natural ecosystems are located. As a whole, the programs of both axis, by December 2011, have supported a total area near 55.6 million hectares (Figure 2.38), which is equivalent to 28.3% of the continental area of the country. From the benefited area to 2011, 57.9% belonged to the Uma (around 32.2 million hectares7), 39.7% belonged to the Prodefor (22.1 million hectares) and the remaining 2.4% (nearly 1.32 million hectares) belonged to the Procymaf.

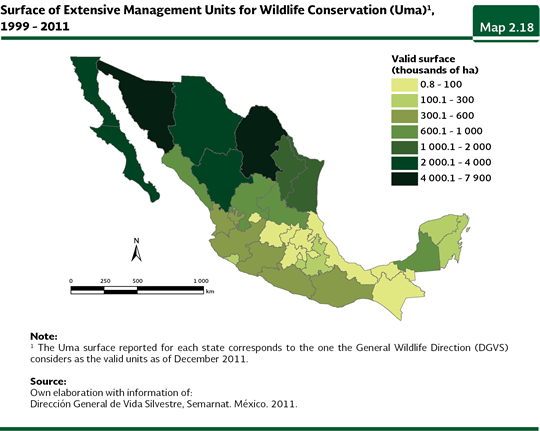

The Management Units for Wildlife (Uma) were established in 1997 and they are coordinated by the Semarnat through the General Wildlife Direction (DGVS, in Spanish). They are aimed at using the wildlife in a legal and viable way, as they promote alternative schemes of production compatible with the protection of the environment, by means of the rational, orderly and planned use of the natural resources. In addition to allowing the sustainable use of the wildlife populations and to generating economic earnings for the owners of the lands where the units are established, this instrument could collaterally conserve the habitat of the object species, necessary to keep the good shape of the used populations, as well as the environment services they provide. The Uma have been focused in the northern area of the country, being the xerophilous shrublands, followed by the pastures and the temperate forests, the main ecosystems benefited by this instrument. The states with the highest accumulated area of extensive valid Uma between 1999 and 2011 were Sonora (7.9 million hectares; 24.5 % of the national area of extensive Uma), Coahuila (4.9 million hectares, 15.1%), Baja California (2.8 million hectares; 8.8%) and Baja California Sur (2.6 million hectares; 8.2%; Map 2.18).

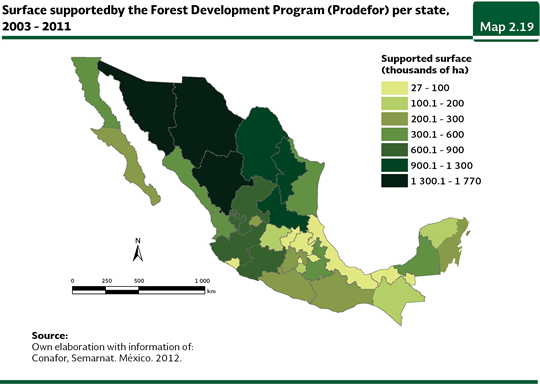

In some cases, the installment of the Uma has been carried out inside the ANP, what has yielded additional benefits, among them, the decrease of the pressure of the communities in the protected areas. Although there is not a recent figure of the Uma area included in the ANP, in 2005 was about 2.5 million hectares; in other words, a little more than 10% of the total area of Uma for that year. More details about the Uma may be found in the chapter Biodiversity in the section Biodiversity protection. The Forest Development Program (Prodefor), started in 1997 and is coordinated by the Conafor in ProÁrbol, attempts to promote the productivity and diversification in the use of the forestry ecosystems, as well as the development of the forestry productivity chain where the use is carried out, which may be through elides, communities and small landholders. This program is coordinated along with the state governments. The Prodefor has grown meaningfully since its establishment: it went from 3 million hectares supported for their incorporation or reincorporation in the 1997-2000 period, to 22.2 million in 2011. The main benefited ecosystems have been the xerophilous shrubs, basically because of their wealth in non-timber products, the temperate forests and tropical forests. The supported area per state between 2003 and 2011 is shown in the Map 2.19. The states with the largest area supported by this program, in that period, were Sonora (12% of the total supported area, 1.76 million hectares), Durango (10%, 1.51 million hectares), Chihuahua (9%, 1.34 million hectares) and San Luis Potosí (7%, 1.1 million hectares).

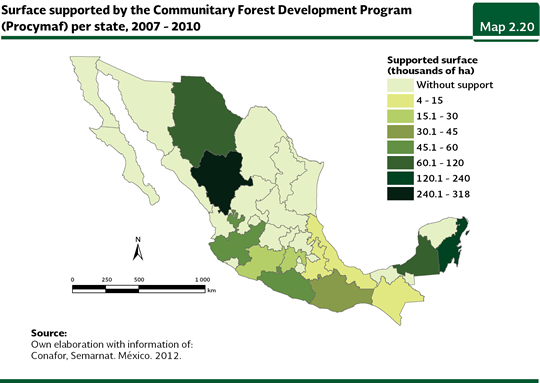

On the other hand, the Communitary Forest Development Program (Procymaf) attempts that ejidos and communities, mainly indigenous, located in priority regions from Durango, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Campeche, Puebla, Veracruz and México, set up practices of sustainable forestry management under schemes of community forestry which generate local development processes. In its first phase (Procymaf I), which started in 1998 and ended in 2003, this program benefited under the concept of a good technical management nearly 272 thousand hectares; while in its second phase (Procymaf II) benefited, between 2003 and 2010, 1.32 million hectares. From the 12 states where the program has been implemented, the ones which included a larger area, between 2007 and 2010, were Durango (little less than 318 thousand hectares, in other words, nearly 36% of the total supported area in the period), followed by Quintana Roo (224 thousand hectares, 25%) and Campeche (nearly 80 thousand hectares, 9%; Map 2.20).

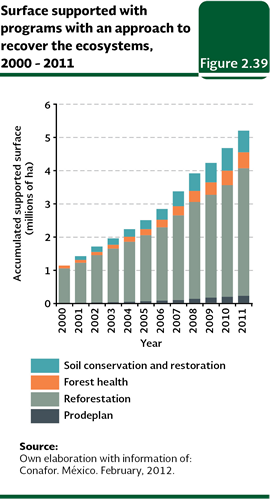

Recovery of terrestrial ecosystems Before the meaningful loss and alteration of the natural ecosystems of the country, it was essential the design and implementation of instruments of environment politics dedicated not just to the protection of the remnants of the ecosystems and the sustainable use of the wildlife, including the forestry activity, but other ones oriented to the recovery, when it were possible, of degraded areas, affected by pests or diseases, or those ones where the natural ecosystems may have disappeared. The principal strategies along this line have traditionally been the reforestation, the boost to the establishment of forestry plantations, the soil restoration, the fight of forest fires and the practices of forestry health. Although some of these strategies are known, such as the reforestation, they cannot return the ecosystems to their original condition, in other words, with their biodiversity and their ecological processes working as they used to before the human intervention they may contribute to stop the environment degradation and to maintain certain basic environment services, such as the recharge of aquifers, for instance. In some other cases, such as the actions to fight the forestry fires, the pests and forestry diseases, a larger loss and alteration of the ecosystems are avoided, as well as their causes, the fire, the pests and the diseases, respectively, be spread damaging larger areas of natural vegetation. The programs to recover the terrestrial ecosystems which were implemented in the country involve the program of Forest Ecosystems Conservation and Restoration Program (Procoref, in Spanish, which involves the Reforestation Program and the actions of conservation and restoration of forestry soils, as well as the actions of forestry health) and the Program for Commercial Forest Plantations (Prodeplan, in Spanish), both of them are included in ProÁrbol and coordinated by Conafor. The accumulated area attended by these two programs as of December 2011, according to preliminary data, rose to a little less than 5.2 million hectares, 74.1% of which corresponded to the reforestation efforts (nearly 481 thousand hectares), 12.5% to forest soils conservation and restoration (nearly 650 thousand hectares) and 4.1% to the commercial forest plantations (around 212 thousand hectares; Figure 2.39). In total, the area attended by these instruments until 2011 reached 2.6% of the national terrestrial area.

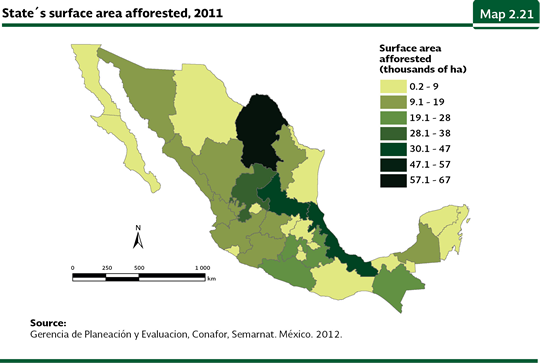

A strategy adopted by the Federal Government to deter and revert the deterioration of the forest cover of the country has been the reforestation. In 1995, it was created the National Reforestation Program (Pronare). With the purpose to obtain and appropriate reforestation in strategic sites; it was transferred, in 2001, to the Conafor and currently it is part of the Reforestation Program, of the Procoref. Nowadays the reforestation works are carried out mainly in disturbed forest areas, with an emphasis in the ones affected by fires, the ones subject to illegal clearing, over grazing and the ones susceptible to restructuring into forestry areas; one part of the reforestation is also carried out in APN. The Program attempts the use of native species appropriated for every ecosystem. In the case of the tropical species, the red cedar, the mahogany, “palo de rosa” and “primavera” are the preferred ones, while for the temperate regions the conifers are the ones chosen, mainly pines. For the semi arid regions, agave8, prickly pears, mesquites, “sotol“and pinion pines. The reforested area in the country has followed a growing tendency from early the 1980 decade until today: while in 1993 nearly 14,500 hectares were reforested, by 2011 a little less than 481 thousand hectares were reached. In this last year, the states where a larger area was reforested were Coahuila (66,561 hectares), Veracruz (40,791 hectares), San Luis Potosí (39,622) and Zacatecas (30,678 hectares; Map 2.21). In contrast, the states with the lowest reforested areas were Distrito Federal (232 hectares) and Baja California Sur (1,562 hectares).

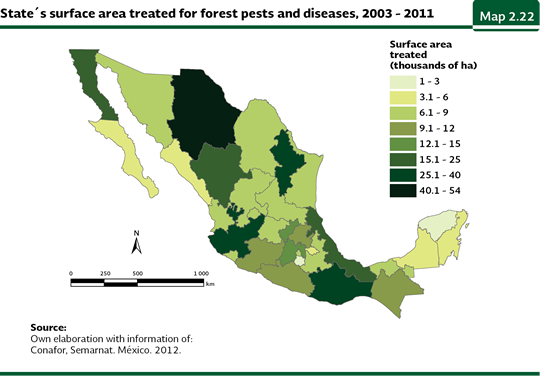

The pests and the forestry diseases may cause serious effects to the ecosystems, an, at the same time, to the rural communities dedicated to the forestry activity. The forestry health activities carried out by the Procoref are aimed, mainly, at preventing and fighting pests and forestry diseases that could have ecological, economic and social impacts. The actions include the phytosanitary diagnostic, which is mainly carried out in the areas of natural vegetation, as well as in forest plantations, tree nurseries, reforested areas and urban areas. Once the diagnostic is made, an in case affected areas are found, the next step is the treatment. Between 2003 and 2011, the average area treated at a national level was slightly more than 43 thousand hectares. The states that treated the largest area, in this period, were Chihuahua (a little less than 54 thousand hectares), Jalisco (nearly 39 thousand hectares) and Nuevo León (31 thousand hectares), while the ones with the lowest areas recorded under the same concept were Morelos (1,296 hectares), Yucatán (2,551 hectares) and Baja California (3,355 hectares; Map 2.22).

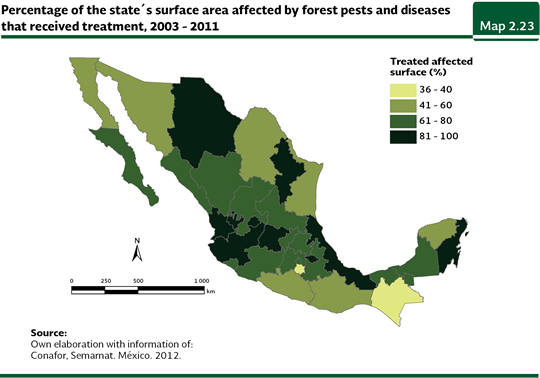

The national effort in the treatment of the areas damaged by pests or forestry diseases is still insufficient, because out of the damaged area, in the period 2003-2011, just a few health activities were carried out in a little over 67% of the area with some kind of damage. The states that treated the highest percentage of their damaged area were Aguascalientes and Nayarit (both of them with the total of the damaged area), Nuevo León (a little more than 97%) and Guanajuato (a little more than 93%). In contrast, the states that treated a lower percentage of their damaged area Morelos (about 36%), Chiapas (a little less than 37%) and Guerrero (about 42%; Map 2.23).

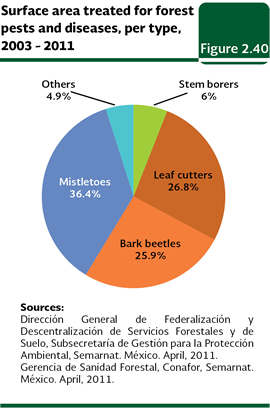

Taking into consideration the treated area, the most fought pests in the period 2003-2011 were the mistletoes with 141,351 hectares (equivalent to 36.4% of the treated area in the period), followed by the leaf cutters (104,242 hectares; 26.8%), the bark beetles (100,583 hectares; 25.9%) and the steam borers (23,249 hectares; 6%; Figure 2.40).

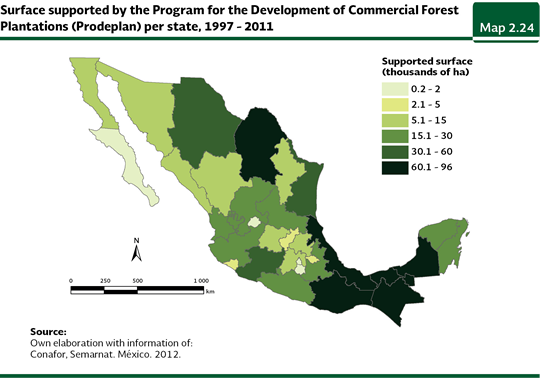

The pressure over the forest ecosystems for the timber extraction and the non-timber products affect the quality of the forests, going from primary forests to secondary forests poorer in species and with altered ecosystemic services. One of the used options all over the world to reduce the pressures over the forest communities has been the establishment of managed systems from where the products extracted from the natural vegetation in an easy and profitable way may be obtained. These systems not just reduce the pressure over the forestry resources, but they also avoid, at the same time, the degradation of the soil and favor the recharge of the aquifer mantles, among other environment services. In the world, since 1990, the forestry plantations have grown at an annual rate of 2.2%, this is, around 4.6 million hectares per year, for a total, in 2010, of around 265 million hectares (UNEP, 2011). In Mexico, in 1997, the Program for the Development of Commercial Forest Plantations (Prodeplan in Spanish) was implemented, which is aimed at supporting the establishment (in non-forest-land) and the maintenance of commercial plantations to reach the self-sufficiency in forest products. This programs has produced outstanding results in the last years: from 1997 to 2011, plantations in over 788 thousand hectares have been supported, covering all of the states in the country, however, Veracruz (with a little more than 95 thousand hectares), Campeche (a little less than 92 thousand hectares), Coahuila (nearly 67 thousand hectares) and Chiapas (66 thousand hectares) were the states with the largest supported area in that period (Map 2.24).

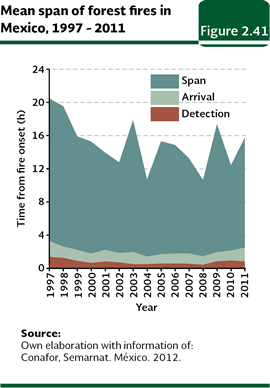

Another front of the fight against the destruction of the vegetal cover of the country is the fight against the forest fires. Its actions involve the prevention, forecast and the direct fight. Among the prevention practices, the firebreak breach and the prescribed burnings, the environmental education and the legal actions are included. For the fire forecasts, the National Meteorological Service provides its support, providing information about droughts and high temperatures. At the same time, and through an agreement with the Ministry of Natural Resources of Canada the Mexico’s Forest Fire Information System is managed. This system releases a fire risk index based on meteorological data, the amount of combustible material and the topography, among some other criteria. Based on this information, a cartographic representation is made which shows the places where there might be more serious fires. The detection of ongoing fires takes place by means of sighting from towers, planes or land vehicles. The University of Colima and the Conabio constantly monitor, via satellite, the “hot spots” of the territory, which are the areas where the fires take place. All this allows arriving as soon as possible, to the affected areas to fight the fire. In the period 1997-2011, the average time to detect fires was 48 minutes, while the arrivals averaged 1.18 hours and the length of the fires was 13 hours (Figure 2.41).

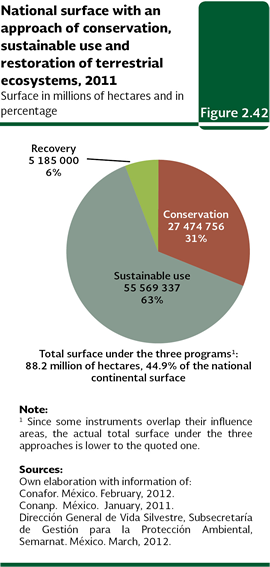

As a summary, as of December 2011, the instruments grouped in the three former lines, conservation, sustainable use and recovery of ecosystems, could have attended, as a whole, an accumulated area of 88.2 million hectares, which would mean 44.9% of the national continental territory (Figure 2.42). Notwithstanding, it is very important to consider that, since some of the instruments overlap their influence areas (i. e. the Uma and the PSAs with the ANPs or the areas which are reforested within the ANP), the area actually attended is smaller.

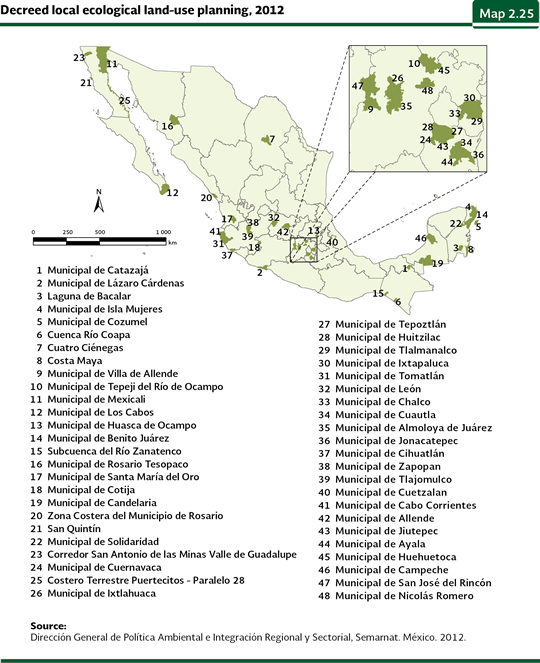

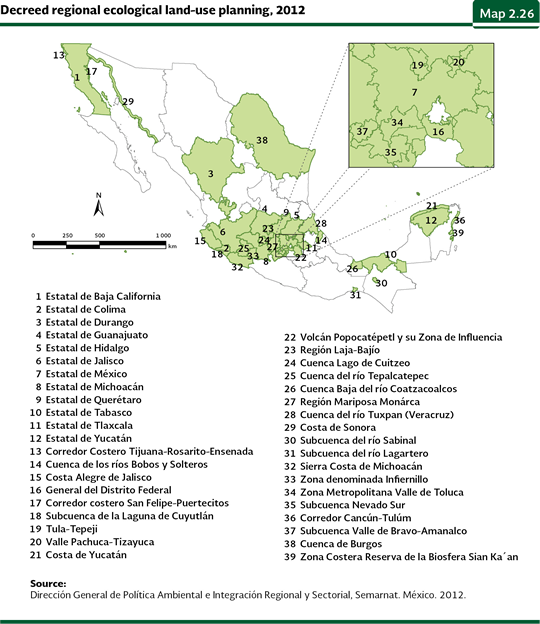

Ecological land-use planning The land use has been mainly ruled by the needs of food, housing, and customs of the society which changed many ecosystems into farming lands, cattle rising areas and urban areas, among some other uses. The environment consequences of such changes, in addition to the loss plant cover, biodiversity and environmental services, brought, in many cases, negative economic and social consequences for many human groups. Nowadays, the establishments of populations in high risk areas, the clear-cutting of forests in mountain areas to favor agriculture fields and the clearance of mangroves for the development of fish farms, are just some examples of the kind of decisions that, made without knowledge of the land aptitude, have caused bigger environmental and social problems in comparison to the benefits they provided. The decision about what use a land must be granted should be determined, at least at some extent, by an “aptitude analysis”, which is a procedure that, based on the environment features of the study area, allows knowing the alternatives of land use, among which are the productive activities, the sustainable use of the natural resources, the maintenance of the goods and environment services and the conservation of the ecosystems and the biodiversity. Despite the fact that such decision is influenced by economic, social or historical considerations, the natural features of a territory play a determining role at defining the limits for the development of the productive activities. The instrument that attempts to conciliate the aptitudes, priorities and needs of the land use, is the ecological use planning, which is legally defined as “the instrument of environmental policy whose objective is to regulate or induce the use of land and the productive activities, in order to achieve the protection of the environment; the preservation and sustainable use of the natural resources, based on an analysis of the deterioration tendencies and the potential uses of these” (General Law of the Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection, Title First, Article 3, fraction XXIV). As the General Law of the Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection (LGEEPA, in Spanish) about the Territory Ecological Land-Use Planning (OET, in Spanish) regulation was published in 2003, the OET focus is aimed at achieving a balance between the productive activities and the conservation of the nature through a participative process where the different sectors of an area subject to management explicitly state their needs and interests (both present and future); and look for, by means of the negotiation and conciliation of interests, the occupation pattern and use of the territory and the regulation that minimizes the conflict among their activities, to adopt it and to be subject to its stipulations. According to the LGEEPA, there are four types of ecological land-use planning programs: 1) the general ecological land use-planning, as an indicative character for the individuals, but compulsory for the Federal Public Administration, which refers to the total amount of territory and which is competence of the Federation; 2) the regional land use-planning, applicable to two or more states, two or more municipalities or to the whole state and whose issuing is competence of the state authorities; 3) the local land use-planning, which is applied in a whole municipality or in a part of the state and whose issuing is competence of the municipality authorities, and 4) the ecological marine land-use, which include the marine areas and the adjacent federal areas which are competence of the Federation (see the Box Ecological marine land-use planning). The Territory´s General Program of Ecological Land-Use (OEGT, in Spanish), published in September 2012, “… establishes the basis that allow the Government Secretariats coordinate with the states and municipalities to elaborate and implement their projects taking into consideration the territorial aptitude, the deterioration tendencies of the natural resources, the environment services, the risks caused by natural dangers and the conservation of the natural estate” (Semarnat, 2012). State agencies and Federal Public Administration entities that carry out activities that have an impact in the occupation of the territory took part in the formulation of the OEGT, implemented in 2008. These secretariats were Environment and Natural Resources; Social Development; Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food; Communications and Transportations; Tourism; Energy; Agrarian Reform; Economy; Government and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, and it received feedback from the authorities in charge of development planning and environment from the states and Consultive Councils for the Sustainable Development. Concerning the local ecological land use planning as of December 2012, the General Direction for Environment Policy and Regional and Sectorial Integration of the Semarnat had a record of 48 already ordered and several more in statement process attended by the municipality governments. Concerning the regional managements, as of the same date, 39 were already ordered and several more were in the statement process attended by the state governments (Figure 2.43). Nowadays, about 39% of the national terrestrial area, in other words, 77.6 million hectares, has an ordered ecological land-use planning either regional or local. Most of the ordered ecological land-use planning are located in the center of the country, the Yucatán peninsula and at the north of the Baja California Peninsula, involving, a large part of them, the participation of the urban and touristic development sector (Maps 2.25 and 2.26). For both peninsulas, through the ecological land-use planning, the preservation of the surroundings is sought, so the destination continues being attractive for the tourists, since this industry is one of the most important income sources in both regions. This does not exclude the participation of other sectors oriented to the ecological preservation and to productive activities, such as the agricultural, fishing and forestry.

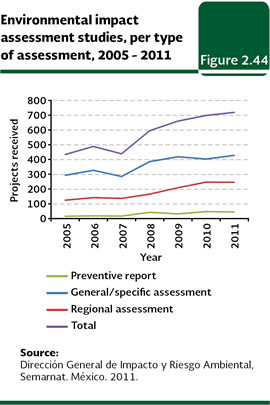

Environmental impact assessment The environmental impact is defined as any change of the environment caused by the action of the man or the nature. However, just the changes caused by the human activities are subject to the evaluation from the Mexican Government. In this sense environmental impact assessment (EIA; in Spanish) is an instrument of the environment policy aimed at a detailed analysis of several development projects as well as of the sites where they would be implemented, with the purpose to identify and quantify the impacts their implementation may cause to the environment. It is possible, with this evaluation, to establish the environmental feasibility of any project (through the cost-environment benefit analysis) and to determine, in case it is required, the conditions for its implementation, as well as the prevention and mitigation measures of the environmental impacts, in order to avoid or reduce at the minimum level the negative effects over the environment and the human health. The environmental impact assessment in Mexico was started in 1988 with the publishing in the Federation Official Gazette of the LGEEPA and its Directive on Environmental Impact Matters. In the Directive, three modalities for the filing of the Environmental Impact Assessment are established: general, intermediate and specific. Likewise, it was determined what type of projects should be subjected to the evaluation procedure of environmental impact, along with the accurate form the information included in them should be presented. On May 30, 2000, the modifications to the Directive on Environmental Impact Matters were published (DOF, 2012), which went into effect as of June 29, 2012. Among the most important reforms are the redefinition of the works and activities subject to the evaluation procedure of the environmental impact of federal competence, which are classified per type of activity, industry or the natural resources that may be affected. In this sense, it was determined that the states and municipalities are responsible of the evaluation of the environmental impact in all those works and activities that are not included in the listing of federal competence. Other of the important reforms were the changes of the general, intermediate and specific modalities, for regional and particular. In general terms, the assessments of environmental impact must be filed in the regional modality when it is about projects which include industrial parks, fish farms of over 500 hectares, highways, railroads, projects to generate nuclear power, dams and, in general, projects that alter the hydrological basins. This modality of evaluation is also required for the works which are programmed to be developed in areas where there is an ecological management program and in sites where accumulative, synergistic or waste impacts are expected which may cause the destruction, the isolation or the fragmentation of the ecosystems. In the other cases the assessment should be filed in the particular modality. It is important to note that whether the project provides activities considered as highly risky, a risk study should be attached to the environmental study for its evaluation and opinion. In order to submit a project to this procedure and obtain the approval, the promoter should submit at the Semarnat a Preventive Report or an Environmental Impact Assessment Statement in the modality that applies according to the Directive Environmental Impact Matters (REIA, in Spanish). Figure 2.44 shows the total filed projects for the evaluation of environmental impact in each modality in the 2005-2011 period (Table D4_IMPACTO00_02).

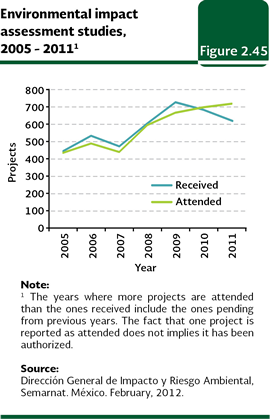

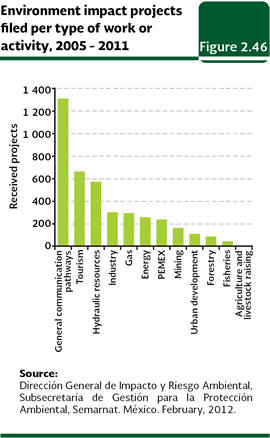

Once the Environmental Impact Assessment Statement is evaluated, the Semarnat issues the corresponding resolution where it denies or authorizes the execution of the project. In case of the approval, this may be granted in the requested terms or if it is considered necessary, noting the conditions or additional measures of prevention or mitigation that should be fulfilled. A requested authorization may be denied in those cases where the applicable laws are not met, when, due to the execution of the project, one or more species may be threatened or put in extinction danger or when there is falseness in the information provided by the promoter. In the 2005-2011 period, 4,072 projects were filed at the Semarnat (582 in average per year) and it attended 4,033 assessment (Figure 2.45; Table D4-IMPACT00_02). Most of the filed projects were for works and other service activities of the sector of general communication pathways (1,314 projects), tourism (665), water resources (575), industrial (305) and gas (297; Figure 2.46; Table D4_IMPACTO00_03).

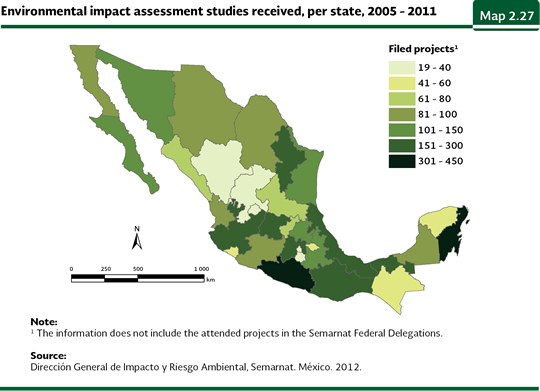

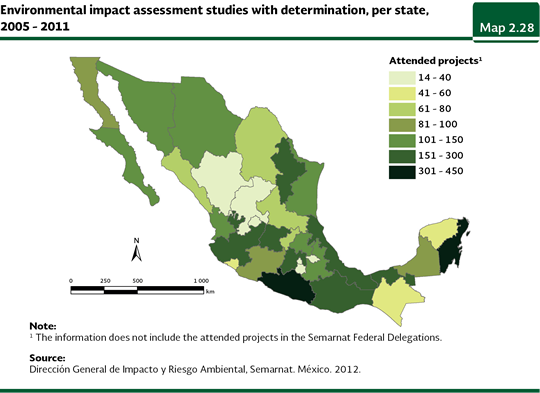

The states which, in the 2005-2011 period filed the largest number of projects to the procedure of environmental impact were Quintana Roo (432), Guerrero (387) and México (278); in contrast, Zacatecas (19), Morelos (22), Aguascalientes (23) and Distrito Federal (27) where the states that had the lowest demand of project evaluation (Map 2.27; Table D4_IMPACTO00_01). The total of attended projects, per state, is shown in Map 2.28.

Notes: 7 The Uma area reported in the text corresponds to what the General Wildlife Direction (DGVS) considers it is part of the valid units by December 2011. Notwithstanding the historical value reported by such Direction, which includes the ones which have written down, accounts, by the same date, an area of 36.1 million hectares. 8 Although agave plants, prickley-pear cacti and other succulent species of arid and semi-arid zones are not trees, these are the most suitable species for recovering these areas for their resistance and role in ecosystems, such as soil protection and runoff control. |