| La información más reciente sobre vegetación y cambio de uso del suelo en México, se encuentra en los Indicadores Básicos y Clave. |

| CHAPTER 2. TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS |

The geographical situation of Mexico, its climate variety, topography and geological history have produced one of the most impressive biological wealth in the world. In addition to the large variety of species of plants and animals, and the important genetic variety that holds, another of its features is the large diversity of plant communities which are found in its continental and insular territory. These range from alpine areas to coastal dunes and wetlands, going through the xerophilous shrublands, temperate forests, tropical forests, mountain cloud forests and natural grasslands. Ecosystems in general, and the terrestrial ones in particular, have been the sustain of the human populations since early times: they have provided them several goods, such as food (meat, fruits, vegetables and spices), timber for construction, wood, paper and fibers for fabrics, among many others. Additionally, these supply environmental services like air and water purification, soil generation and conservation, waste breakdown, nutrient recycling and transfer, protection of littorals against wave erosion, partial climate stabilization and buffering against extreme climates and their impact, just to mention some of the major contributions. The huge global population growth that took place during the 20th century, along with an unprecedented industrial and urban development, brought about the most significant transformation of terrestrial ecosystems ever recorded by the mankind. According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), for 2000, 42% of the world forests had been transformed, as well as 18% of arid areas and 17% of insular ecosystems, mainly to farming and pasture areas; others were cleared to develop towns and cities, build roads, electricity power infrastructure and water reservoirs. Mexico has been no exception in this process of terrestrial ecosystem degradation and loss. A significant proportion of the country’s area has been transformed into agriculture land, grasslands and urban and rural areas. Some ecosystems that previously comprised extensive areas of the country have been reduced today to small remnants keeping the original characteristics plus broad areas of degraded land. This chapter describes the current state of the national terrestrial ecosystems, with a particular emphasis on the processes and factors which have promoted their transformation and changes in the recent decades. It has also been included a section with aspects related to their use, mainly referred to the exploitation of the timber and non-timber forest products. The final section deals with the government responses aimed at the preservation of the remaining natural vegetal cover, as well as those focused on the recovery and sustainable use of natural resources present in the country’s terrestrial ecosystems.

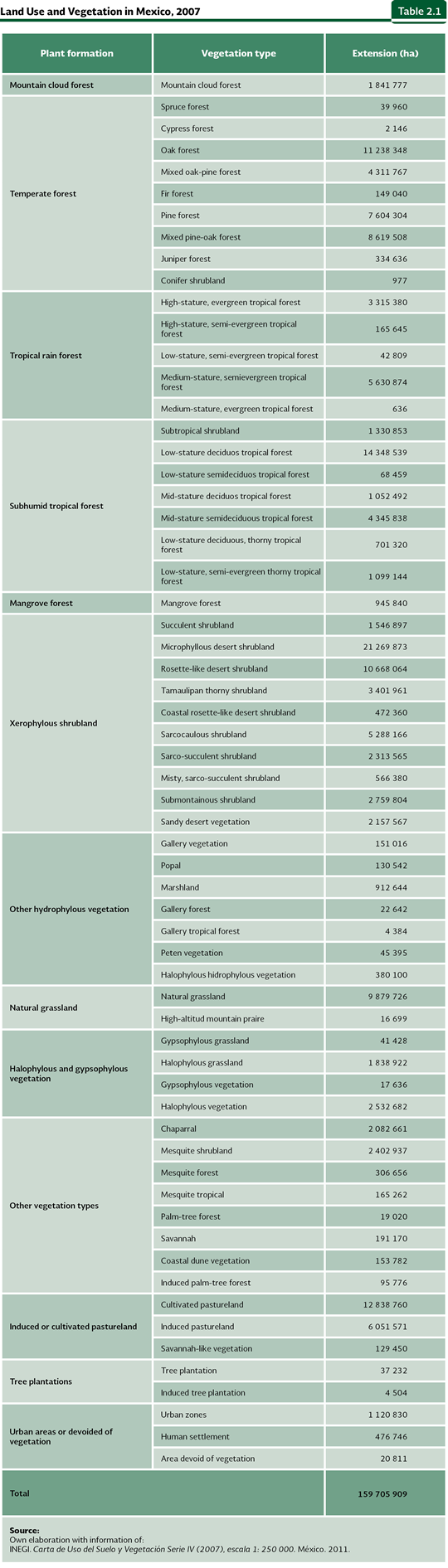

NATURAL VEGETATION AND LAND USE IN MEXICO The way in which a piece of land and its plant cover are used is known as “land use”. The most recent evaluation of land uses in Mexico corresponds to the Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación Serie IV (scale 1:250,000), elaborated by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI in Spanish), which describes land use and vegetation for 2007. Given the large number of vegetation types and land uses mentioned in this chart, its aggregation with analysis purposes becomes indispensable. Aggregation of vegetation types may be done using different criteria: floristic composition, physiognomy or their usefulness from forestry perspective, among others. The latter criterion has important repercussions in the statistics because prevents comparison with figures obtained with other aggregations. In this work, vegetation was classified following the physiognomy criterion, just as it is shown in Table 2.1. For further information on the characteristics of some types of natural vegetation, refer to the Box The Vegetation of Mexico.

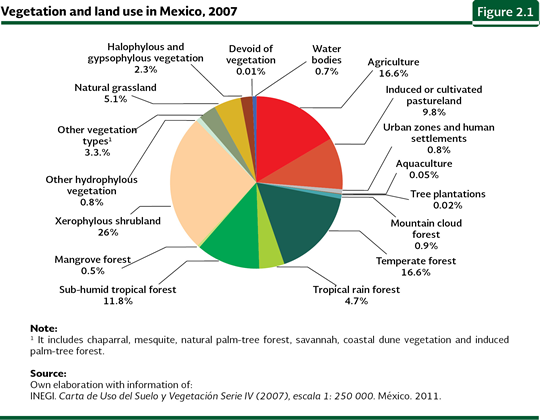

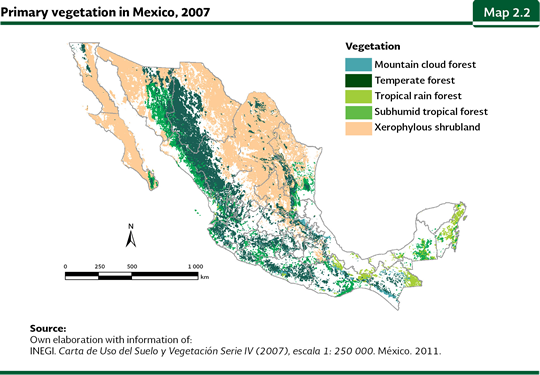

According to the series IV, 71.8% of the country (about 140 million hectares) was covered by natural communities in 2007; the remaining land, a little more than 56 million hectares (about 28% of the territory), had been converted to farmland and urban areas and other anthropic covers. In the same year, shrublands were the predominant plant formation (36% of the remaining natural area which is equivalent to nearly 26% of the territory), while forests (both temperate and mountain cloud forests) and the humid and sub-humid tropical forests, jointly accounted for 34% of the national territory (34 and 32 million hectares, respectively; Figure 2.1).

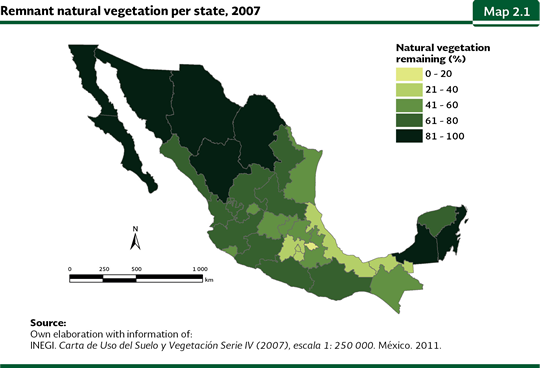

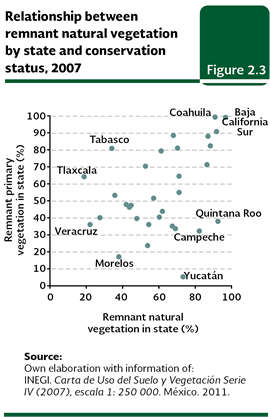

The states with a highest proportion of land covered by natural vegetation (regardless of its degree of conservation) were Baja California Sur (97%), Quintana Roo (93%), Coahuila (92%), Baja California (91%), Chihuahua (88%) and Sonora (87%; Map 2.1). In contrast, in Tlaxcala (19%), Veracruz (22%), Distrito Federal (28%), Tabasco (34%), Mexico (36%) and Morelos (38%), natural vegetation covered less than 40% of the area in each state.

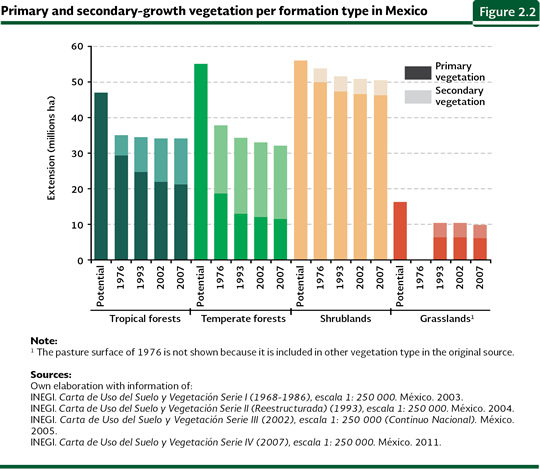

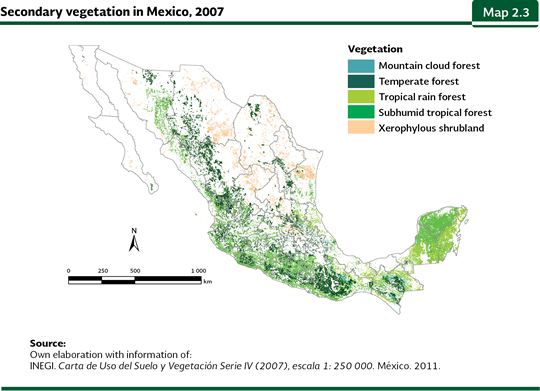

However, in 2007, not all of the remaining natural vegetation was well preserved; just 69.5% (equivalent to 49.5% of the national territory) maintained primary vegetation. This condition corresponds to vegetation where most of the species present in the original ecosystem still remain there, with no signs of substantial disruption and which is, in principle, the one with the greatest importance in terms of biodiversity and supply of environmental services. In 2007, tropical forests were the ecosystems most affected by degradation, because about 36% of their area (11.5 million hectares) corresponded to a primary condition (Figure 2.2, Maps 2.2 and 2.3). For temperate forests, in the same year, 62% of its area (slightly more than 21 million hectares) remained as primary; as a way of comparison, in 2010, in the world, 36% of the existing forests1 were primary (FAO, 2010). The vegetal formation with the minor degraded area in the country in 2007 was the shrubland, which is calculated in about 8.5% of its remaining area (4.3 million hectares), although it could be higher because many shrublands are subjected to extensive cattle raising and it is difficult to identify their deterioration level without an extensive field sample which may support it.

In general, the states with a high proportion of natural cover keep a significant percentage of primary vegetation. For instance, nearly 99% of the remaining natural vegetation of Baja California Sur, which covers about 97% of the state, is primary (Figure 2.3). However, exceptions to this tendency may be observed: there are states with large areas of remaining natural vegetation in secondary condition, for instance, Quintana Roo (with just 38% of its primary vegetation), Campeche (32%) and Yucatán (5.4%). In contrast, Tlaxcala and Tabasco keep high percentages of primary vegetation (64 y 81%, respectively) in spite of its much undermined primary vegetation (18 and 34% of their areas, respectively).

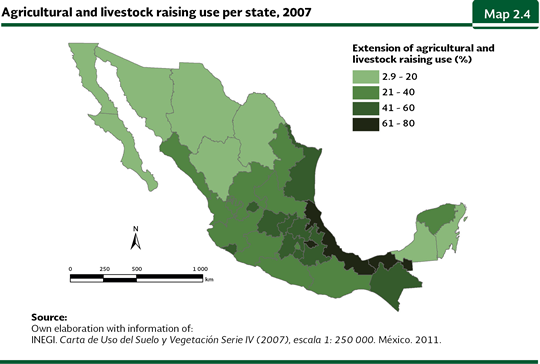

With respect to productive systems, according to the series IV, farming lands and cultivated and induced pastures (the latter used in cattle raising) covered, in 2007, slightly more than 51 million hectares, in other words, around 26% of the territory. Out of this area, 63% was for farming land and the remaining 37% to induced and cultivated pastures. The states which have transformed a larger area of their ecosystems to use them for farming and livestock activities are those located in the Gulf of Mexico littoral and in central Mexico: Tlaxcala (nearly 80% of its area), Veracruz (77%) and Tabasco (65%; Map 2.4). On the contrary, the states with the lowest farming area were Baja California Sur (a little less than 3%), Quintana Roo (6%), Coahuila and Baja California (each one with nearly 8%).

Nota: 1 According to FAO, forests are defined as vegetation covering more than half an hectare of the area, including trees more than 5 meters high and a with canopy covering at least 10%, or with trees capable of reaching these minimum limits in situ. This definition does not include land subjected to predominantly farming or urban uses. For this reason, the “temperate forest” and ”rainforest” categories in the classification system used in this chapter are included within FAO’s forest category.

|